That’s it – the end of this blog. Nothing more to say.

Why? Because tomorrow is my submission deadline for Digital Textualities? Perhaps – but also because, thanks to Jonathan Basile, it seems there will soon be nothing new I, or anyone, can think of.

But first, a little background. One of the central texts on this module has been Jorge Luis Borges’ “The Library of Babel” – an infinite library (how wonderful!), containing not only all possible human knowledge, but all possible combinations of all the characters of human language*. As Borges’ librarian puts it,

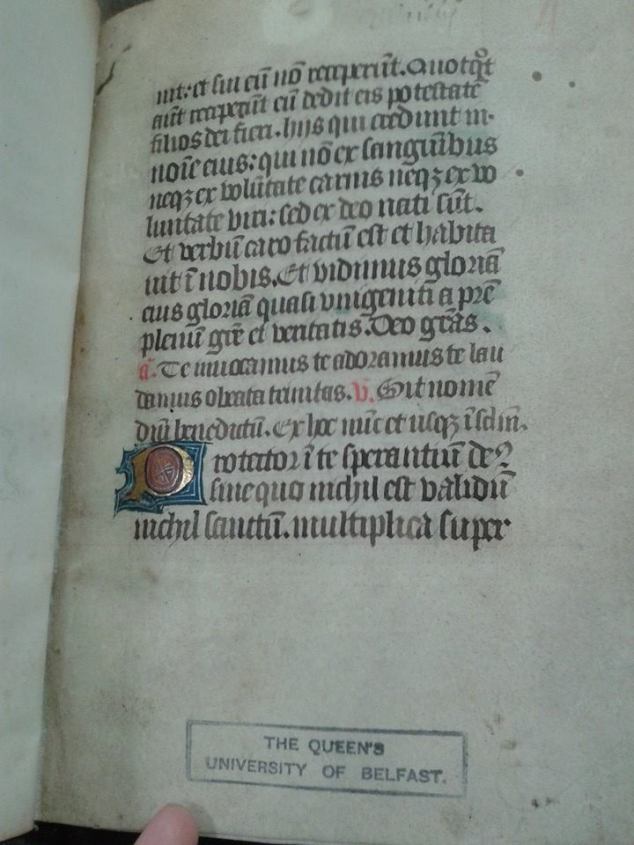

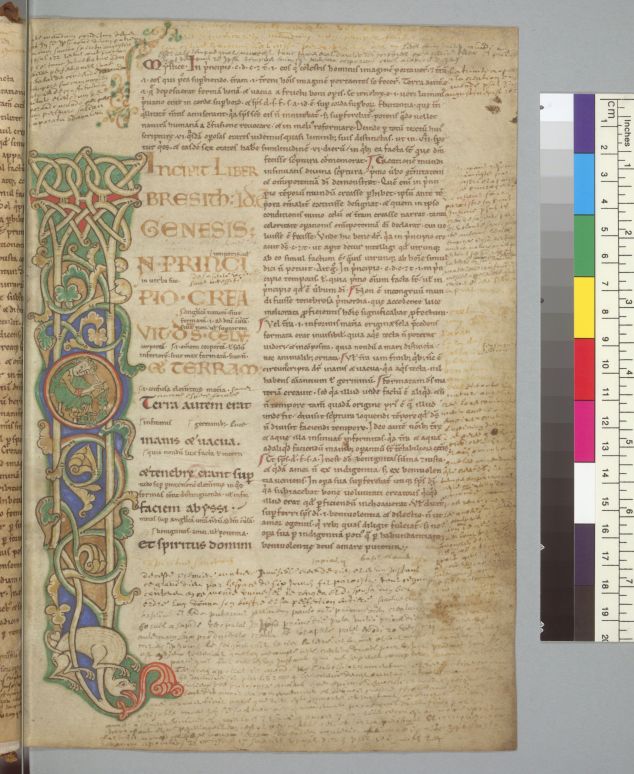

In all the Library, there are no two identical books […T]he Library is “total” – perfect, complete, and whole, and that its bookshelves contain all possible combinations of the twenty-two orthographic symbols* […T]hat is, all that is able to be expressed, in every language (114-5).

*Despite the vastness of Borges’ vision, it does appear that he has forgotten the great number of languages which do not rely upon the Roman alphabet.

It is an utterly brilliant idea. It reflects the idea that everything we think and say has already been thought and said before; we are only unaware of it because all these thoughts and speeches have not been recorded. Borges offers us a written equivalent of this idea: all of time and space, all of humanity’s history and future, contained within books.