Last week, I gained access to the literary Fort Knox that is the McClay Library’s Special Collections. It took some time to sort the visit out – not least because I couldn’t work out how to open the door.

Now, why did I choose to embarrass myself trying to get into my library’s inner sanctum?

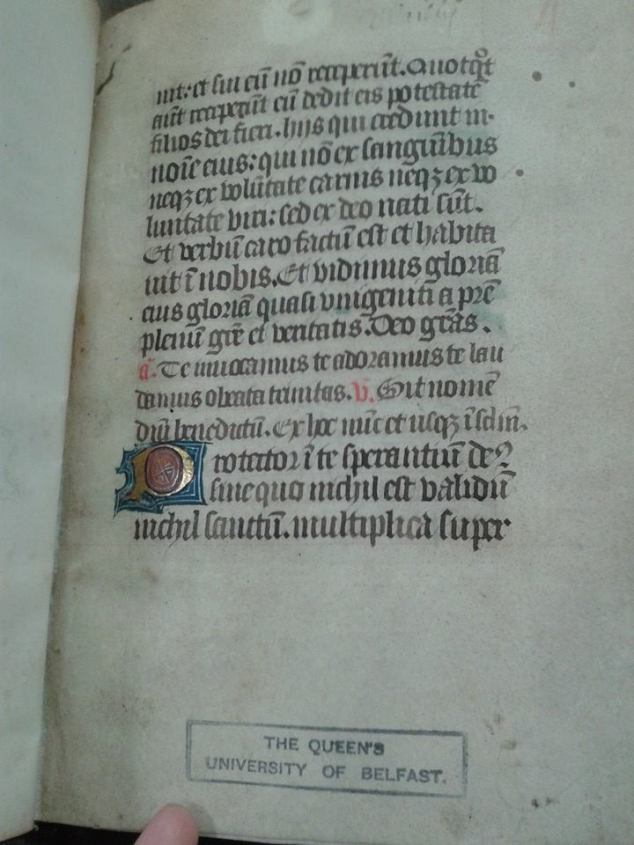

For this, of course:

This beautiful book goes by the rather snappy name of Manuscript 1/17. It’s a Book of Hours, handwritten in the 15th Century on vellum. We were shown it in our first week of class, and being as obsessed with old books as I am, I had to take another look.

I’ll be writing a few posts about this wonderful little item over the next few weeks, but first, I thought I’d best take a quick look at what a Book of Hours actually is.

Basically, a Book of Hours was used by lay Christians to help them in their daily devotions, featuring both biblical material and details of saints (Groag Bell, 753). It was based on the liturgical calendar used by members of religious orders (known as the Divine Office), and so contains different sections to be read during different parts of the year, such as Advent. The ‘Hours’ part refers to the fact that the text also contains different prayers and devotions for different parts of the day, from matins through to compline.

Kathleen Ashley notes how, ‘[a]s a broad genre, Books of Hours were made for and owned by all the upper classes in society’ (150). They were also particularly popular with women, and were often used by young girls as they were learning to read, or given to brides (Groag Bell, 753).

This particular Book of Hours is ‘of Rouen use,’ meaning that the particular saints referenced have links to that region of France. It also isn’t in too great a condition – all of its images have been removed, as have the first few leaves (pages). The above image is the first remaining leaf, which explains why the first word isn’t illuminated as one would expect. On that note, I should add that I deliberately didn’t photograph the cover of the book, as it was rebound in Russia in the 19th Century – no medieval binding to be seen.

Still, it’s a fantastic and fascinating artefact (even if I can’t read a word of it). Over 600 years ago, someone would have carried this around with them, regularly reading sections just as we carry our phones around and regularly check BBC News or Facebook.

In fact, for that very purpose, some Books of Hours had ‘girdle bindings:’ leather coverings which ‘extended downwards below the boards [of the cover] as a flap or pouch […] which could be slipped under the reader’s belt so that the manuscript hung upside down at the waist’ (Clemens and Graham, 55). Thus the Book of Hours could be truly portable, ready to be opened whenever its owner fancied a little bit of devotional reading.

Manuscript 1/17 isn’t so portable any more: I think if I tried to take it out of Special Collections I would have been rugby-tackled by several angry librarians.

But, of course, this is the 21st Century. If you really want to live like a medieval lay Christian and delve into a Book of Hours through the day, someone has someone has kindly created a digital hypertext version, complete with a Modern English translation, so you can check out your liturgical calendar on your iPhone.

Book of Hours? There’s an app for that.

Print bibliography:

Ashley, Kathleen. “Creating Family Identity in Books of Hours.” Journal of Medieval and Early Modern Studies. 32.1 (2002): 145-165

Clemens, Raymond and Timothy Graham. Introduction to Manuscript Studies. Ithica: Cornell University Press, 2007.

Groag Bell, Susan. “Medieval Women Book Owners: Arbiters of Lay Piety and Ambassadors of Culture.” Signs. 7.4 (1982): 742-768.

2 thoughts on “Half an Hour with a Book of Hours”